After the Hospital, A Guide to Rehabilitation for GBS

The progression of disability during the acute phase of Guillain-Barré Syndrome can vary from a few days to four weeks, and, infrequently, six weeks. Then a low stable level of impairment (paralysis, weakness, etc.) continues for a variable time, days to weeks, and, less often, months or longer.

When the patient has recovered from acute life-threatening complications such as breathing difficulty and infections, and muscle strength has stabilized and perhaps even begun to return, treatment in an acute care hospital is usually no longer required. However, many patients will still require rehabilitative care including intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Where this care is provided will depend in part on several factors. Choices available for further rehabilitation include:

- In-patient care in a rehabilitation hospital. A common requirement to justify this intensive rehabilitation is the patient’s ability to participate in at least 3 hours of therapy daily.

- Sub-acute rehabilitation, in a nursing/rehab facility.

- (So-called) Day hospital care. The patient sleeps at home and is transported, by a wheelchair-accommodating van, to the rehabilitation hospital or center regularly (daily) for daytime therapy.

- Out-patient rehabilitation.

- Home-based therapy, via visiting therapists or by following instructions set up by a therapist for a home therapy program.

The decision as to the type and location for rehabilitation should be individualized to each patient’s particular needs, considering factors such as overall physical condition, strength, endurance, amount of return of use of arms and legs, and insurance. For example, patients with mild impairment, who can walk with the assistance of a quad (four-footed) or straight cane may not need an in-patient rehabilitation facility and may obtain sufficient care in an out-patient setting. In contrast, patients who can’t walk, or require substantial assistance to do so, but are showing some improvement, may be transferred to an in-patient rehabilitation hospital setting for optimal care. Physicians may occasionally be reluctant to place Guillain-Barré Syndrome patients in rehabilitation hospitals because of concern about depression or relapse of symptoms that could require readmission to an acute care facility for further treatment.

Regardless, transfer of a patient to a rehabilitation center should be considered as a positive next step in the patient’s recovery.

The rehabilitation process itself does not improve nerve regeneration. Rather, the major goal of rehabilitation is to assist the patient in optimal use of muscles as their nerve supply returns, and to adapt to a lifestyle within their functional limitations. In addition to helping the patient regain use of muscles, the rehabilitation center treats any remaining medical complications. These can include control of high blood pressure, antibiotics for infections, treatment or prevention of blood clots, etc.

Strength usually returns in a descending pattern, so that arm and hand strength usually returns towards normal before leg strength. Often, right-handed persons note more rapid return of strength to the left side and vice versa. As arm strength returns, the patient is again able to perform some restricted things that used to be taken for granted, such as brushing their teeth, feeding, grooming and dressing themselves, cutting meat and so forth. As ability to perform activities of daily living improves, the success can be emotionally gratifying.

Rehabilitation in many centers is accomplished by the coordinated efforts of several groups of professionals in a team approach. The team members may include, depending upon the particular patient’s needs, a physiatrist (rehabilitation doctor), physical therapist, occupational therapist, registered nurse, neurologist, internist, psychologist, social worker, etc. Each team member contributes their specific expertise and experience to the patient’s care. Team conferences may be held at intervals, for example, weekly, to assess the patient’s status, determine progress and plan further care. The team’s overall goal is to assist the patient to maximize use of returned function and ultimately return to normal activity. Most patients will eventually lead a normal or near normal life. For those patients with incomplete recovery, the goal is to adapt their lifestyle to their persisting functional limitations.

The physiatrist (pronounced: fiz-eye’-a-trist) (not to be confused with a psychiatrist) is a physician who specializes in physical medicine and rehabilitation. A physiatrist usually coordinates and oversees the total rehabilitation program.

Principles of Rehabilitation for the GBS Patient

During the rehabilitation process, certain issues are unique to GBS patients. Most rehabilitation patients are exercised to maximum ability, to fatigue. This should be avoided in GBS patients as exhaustion requires some time to resolve and will delay the rehabilitation process without benefitting the patient. Substitution of stronger muscles for weaker ones will delay uniform return of strength and optimal function. The physical therapist should be cognizant of the potential for substitution and customize exercises to strengthen weak muscles. Neuropathic pain can limit the patient’s ability to undergo rehabilitation and should be recognized and adequately treated.

Occupational Therapy

An occupational therapist instructs the patient in exercises to strengthen the upper limbs (shoulders, arms, hands and fingers) and help prepare them for return to their occupation. Usually arm strength and use returns before hand and finger dexterity. Help is given to re-learn activities previously taken for granted such as holding a pencil, using an eating utensil, etc. Muscle testing may be performed, and exercises designed to strengthen the weaker muscles. Repetitive squeezing of a rubber ball or putty can strengthen the hand grip while spreading two fingers apart against a rubber band placed across the fingers can be used to increase finger strength.

Tests may be utilized to determine the status of hand sensation. For example, the patient may be instructed to look away or close their eyes while articles of varied consistency and shape are placed into their hand are placed into their hand, such as a marble, key, eraser, pen, closed safety pin, and the like. The ability of the patient, without looking, to discern the presence of these objects and identify what they are indicates that their sensory nerves can perform fine touch discrimination. In another test, the patient inserts their hand, with eyes closed, into a bowl of sand or rice containing such items as chalk, keys, eraser, etc. The ability of the patient to locate these, and, upon removing them, identify their particular shape and consistency provides an index of return of finger sensation. Some patients may experience persistent difficulties in using their hands and fingers to perform such activities as using a zipper, buttoning a shirt, writing, using utensils and handling coins. Methods are available to compensate for these problems. For example, to circumvent difficulty in buttoning clothes, a button-hook device may be utilized. Velcro® straps or zippers with large pull handles may sometimes be practical alternatives to buttons. Because of the potential for fatigue, severely affected patients are taught energy conservation techniques that include using shortcuts to maximize hand and arm use. Splints may be used to position the wrist in a slightly bent position, and to support the thumb, to optimize hand use.

Physical Therapy

The physical therapist emphasizes strength and function of the lower limbs, and ultimately teaches the patient to walk as independently as possible. A variety of methods are used to accomplish these goals. Initially, the patient, fitted with a life jacket (personal flotation device), may be lowered into a pool, and assisted into a suitable depth of water so they can walk on the bottom of the pool with partial weight bearing, the life jacket and water providing buoyancy to enable this. Immersion in a therapeutic pool may also relieve muscle pain. As strength returns, exercises are performed on mats to help strengthen various muscle groups against gravity and resistance. For example, the patient may be placed on a mat on his back, with the knees raised on a triangular foam support; progressively increasing weights are placed on the ankle and the patient is directed to slowly and repeatedly straighten and lower the leg. This exercise can help the patient increase thigh muscle endurance. Slowly raising and slowly lowering the leg affords greater use of muscles and facilitates better development of thigh muscle strength, rather than allowing the lower leg to fall with gravity. Other exercises are used to strengthen the hip musculature, such as lifting the upper leg with the patient on their side and maintaining it in an upward position against gravity.

As nerve innervation returns, other exercises can be used to maintain muscle strength. A stationary rehabilitation exercise bicycle may be used to apply an adjustable force to the leg as it pedals the bike, thus providing progressive resistive exercise to improve strength and endurance.

As leg strength improves sufficiently for the patient to bear weight and begin walking, assistive devices provide added support and balance. The patient may be placed between two railings, called parallel bars, positioned at about waist level. These provide the patient with maximal support while walking, by their holding the bars with both hands. Their upper body can support some of their weight, that their legs no longer have to support. As balance improves, a wheeled walker may be used. The patient rolls or slides the walker forward to provide support as they walk. As balance improves further a standard, non-wheeled walker can be used with the patient lifting the walker forward and placing it down ahead repeatedly as they walk. The next progression may then be to the use of forearm crutches or directly to the use of underarm crutches and then canes. A quad cane, with four small feet close together, provides a fair amount of stability. If the patient has enough balance and strength, a straight cane may be sufficient. Eventually, if possible, independent walking without an assistive device is accomplished. During the rehabilitation process emphasis is placed on proper body mechanics, avoidance of substitution of stronger muscles for weaker ones, prevention of muscle strain and fatigue, and safety.

For patients with persisting muscle group weakness, various methods (orthotic devices) can be used to increase function and independence. For example, a “foot drop” can be treated with a molded ankle foot orthosis (MAFO), a thin lightweight plastic device that fits behind the lower leg and under the foot. For the patient with a weak grip, utensil handles can be wrapped with a thick cylinder of foam rubber to enable better gripping of the utensil; the edge of a plate can be fitted with a metal wall so the patient can push food against it with a fork or spoon to help get the food onto the utensil. A Velcro® strap around a cane handle can hold the hand of a patient with a poor grip onto the handle and enable him to use the cane. Progressive resistive exercises may be designed to strengthen specific muscle groups and functions. In addition to occupational and physical therapists, other persons may participate in rehabilitation, including speech therapists, nurses, social workers, and psychologists. The latter can play an important role in assisting the patient and family in dealing with the new and sometimes overwhelming problems of paralysis, dependency, lost income, and a multitude of associated emotional problems including frustration, depression, self-pity, denial, and anger. Since the prognosis for the Guillain-Barré patient is optimistic, in spite of the potential gravity of the illness, a practical approach is to take one day at a time. Recovery, although greatest during the first year, can continue over two to five or more years. Participation in active physical therapy can be a positive factor in a patient’s recovery both mentally and physically.

Speech Therapy

Speech is impaired in about 40% of GBS patients. Patients on a respirator will be unable to speak because the tube placed into the airway does not allow the vocal cord movement required to produce speech. These patients can usually communicate via Communication Cards. Typically, after an endotracheal tube is removed, the patient’s speech returns within a few days. Even off a respirator, a patient may still have difficulty talking if the muscles used for speech are weak. These muscles control the vocal cords, tongue, lips, and mouth. Slurred speech or difficulty swallowing may occur. A speech therapist can help the patient learn exercises for the affected muscles, to improve speech patterns and clarity of voice, as well as recommend dietary changes to facilitate safe swallowing with adequate nutrition.

Long-Range Plans

As the patient progresses through the rehabilitation program, it may be appropriate to plan for multiple long-range problems. These problems include learning to drive and using convenient parking, re-employment, learning to pace activities, sexual activity, limitations of the wheelchair-bound patient and so forth. A social worker may assist in handling many of these problems. The majority of patients who were in a rehabilitation center may be placed on an out-patient therapy program when sufficient strength has returned. At home, living on a floor that has a bathroom and bed may be temporarily helpful until the patient is able to climb stairs. As sufficient strength returns, driver retraining may be appropriate, especially if the patient had been hospitalized and not driving for a long time. Driver retraining, and adaptation of an automobile for hand controls, is available through some rehabilitation and hospital centers.

The frustration of physical exhaustion, or shortness of breath associated with prolonged walking, may be reduced in the recovering patient by parking near a building entrance in a handicapped parking space. A special parking placard or license plate is available in some states.

As the patient approaches the end of in-hospital rehabilitation, it is usually appropriate to plan for return to their employment or reemployment. This is hopefully a cooperative effort between patient, social worker, current employer and, if available, a state bureau of vocational rehabilitation. A potential barrier to returning to work, as well as resumption of a normal overall lifestyle, is the onset, following a certain amount of activity, of muscle aches, physical exhaustion, and abnormal sensations, such as tingling and pain. These problems may be circumvented by returning to work part-time initially, and if possible, timing activity with intermittent periods of rest. Many patients learn by trial and error how much activity they can tolerate.

After discharge from a formal hospital-based in or out-patient rehabilitation program, there is often a role for continued exercise. Usually, some of the physical and occupational therapy exercises done as an inpatient can be performed at home. Also, activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing, walking, and stair climbing may suffice as a practical outpatient exercise program. Should muscle or joint cramps or aches develop with activity, over-the-counter mild

pain medications such as aspirin or acetaminophen (Tylenol®) may provide relief. Since pain relief does not relieve the muscle, tendon, or joint strains, rest periods or a temporary reduction of activity may be helpful.

Some caution is warranted with respect to the gradual institution of non–hospital-based exercise programs, jogging, and sports. Each recovering patient should be evaluated for their individual needs. Care should be taken to gradually expand activities to avoid tendon, joint, and muscle injury. Upon discharge, the patient can usually resume sexual activity. Positions that minimize muscle exertion, such as lying on the back, may prevent exhaustion until pelvic and other muscle strength has improved. A male patient that experiences erectile dysfunction not present prior to GBS should have his physician review his medications to screen for those that might inhibit normal erections or see a urologist experienced in these problems. In some cases medications for erectile dysfunction, such as sildenafil (Viagra®), may be helpful.

For the wheelchair-bound patient, architectural barriers (e.g., stairs) may be overcome by ramps to enter the home and other buildings. One-floor living, a stair lift, or an elevator may be required. A visiting nurse and physical therapist can treat the patient at home. Significantly handicapped patients are referred to their local rehabilitation center or other resources.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a common problem during the early part of recovery and can even persist in some patients who appear to have recovered. Such patients may have normal strength with standard testing of muscle function, and can perform normal activities, such as walking. Yet, with sustained activity, they may develop weakness or fatigue, and even frank exhaustion and collapse. Fatigue may be preceded or accompanied by flare-ups of muscle pain, or abnormal sensations such as tingling. This problem of persisting poor endurance and fatigability in people with prior GBS was documented in a study of members of the United States Army who had apparently recovered . Despite some people having been able to return to their usual activities, formal physical fitness testing (a 2-mile run, sit-ups and push-ups) showed that some “recovered” patients still had decreased endurance compared to their abilities pre-GBS. Two of the studied patients had normal electrodiagnostic tests (nerve conduction velocity-electromyography), despite having diminished endurance capacity. In summary, both patient and physician should realize that limited endurance is a valid, persisting problem in recovered GBS patients that is difficult to measure objectively with standardized office tests of muscle strength. At least one study suggests that formal endurance exercise training may help improve a patient’s work capacity. Another study showed that three, 20 minute aerobic courses of exercise per day also improved the symptoms of fatigue.

As noted in the “Long-Range Plans” section, if a GBS patient senses impending weakness or, by experience, learns to recognize a flare-up of abnormal sensations that signal impending fatigue, the practical treatment is for them to learn how to pace their activities by resting as needed, to avoid exhaustion. Decreased endurance may necessitate a shortened workday or, alternatively, a less physically-demanding job.

Natural History and Prognosis

The overall outlook for most GBS patients is good, but the course of the illness can be quite variable. An occasional patient may experience a mild illness, with a brief period, days or weeks, of a waddling or duck-like gait, and perhaps some tingling and upper limb weakness. At the other extreme, more often in the elderly, the patient may rapidly develop almost total paralysis, respirator dependency, and life-threatening complications, such as abnormal heart beat and blood pressure, lung congestion, and infections. Rarely, paralysis may be so complete that the patient may not even be able to shrug a shoulder or blink an eye to communicate. The patient is said to be ‘locked in.’ Fortunately, hearing is usually preserved, enabling the patient to hear and fully understand those around them, despite not being able to respond at all. Thus, as always, conversations about problems may best be spoken away from the patient.

Estimates of outcomes are based on several studies. Up to 80 percent of patients will be able to walk without aid at three months after onset of their symptoms, and by the end of a year will experience only minor residual symptoms, such as numbness of the bottom or ball of the foot. A full recovery can be expected, eventually. A patient may experience persisting, but mild, abnormalities that will not interfere with long-term function. Examples include abnormal

sensations such as tingling, achy muscles, or weakness of some muscles that make walking or other activities awkward or difficult.

At least 20% of patients have significant residual symptoms and these patients benefit the most from treatment intervention to modify the immune system. Perhaps 5 to 15 percent of GBS patients will have severe, long-term persisting disability that will prevent complete return to their prior lifestyle or occupation. Factors that often predict greater severity of the disorder, with a longer course and incomplete recovery, include older age, more rapid onset of symptoms, becoming respirator dependent within 7 days and preceding diarrhea. Such patients are more likely to have a prolonged hospital course followed by rehabilitation for 3 to 12 months and may never be able fully to walk independently.

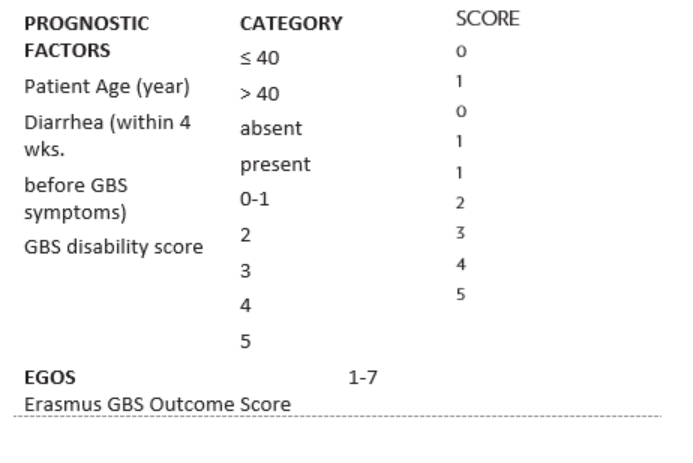

Strength returns at various rates. Some generalizations about speed of recovery can be made based upon the data published in 1988 by the Hopkins-based GBS Study Group and by the 2007 Erasmus University study in the Netherlands. In the latter study patients, were scored based upon their age, preceding diarrhea, and degree of weakness. The patients who could readily walk without assistance were assigned a disability score of 1. Non-walking patients were given a score of 5. The total score can range from the least impaired, 1, to the most impaired, 7. Patients with a low score of 1-3 have an excellent (95%) chance of recovery, being able to walk unassisted within 3 months from onset of their illness. Those with a score of 7 are less likely to have a good recovery. The scoring system they used is summarized in Table 4 (on page 42).

Children with GBS seem to fare at least as well as do young adults, and some studies suggest that pediatric patients actually recover faster and more completely than young adults, who, in turn, appear to recover faster than older patients.

Since GBS rarely strikes twice, if, after recovery, a patient again develops abnormal sensations, it is usually appropriate to look for causes other than Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Evaluation by a neurologist would be warranted. Sometimes, for example, there may be a need for a repeat nerve conduction velocity test, a glucose tolerance test, and other studies to confirm the presence of nerve damage and then to look for its cause. Recurrence or persistence of abnormal sensations or weakness may also conceivably signal the development of chronic idiopathic relapsing or progressive polyneuritis. These disorders are rare and the persistence or redevelopment of abnormal sensations should not be taken as an indicator of the presence of this disorder unless a neurologist experienced with chronic relapsing polyneuritis confirms the diagnosis. This disorder is CIDP.

Immunization Safety

Foreign Travel

Since the illnesses prevented by immunizations often lead to substantial medical complications, the benefits of most immunizations outweigh their risks, even for someone with a history of GBS. Most immunizations and medications used for foreign travel (outside the USA) are safe and mentioned at the end of this section.

Influenza vaccine. The influenza vaccine developed in 1976 for a swine- influenza-derived virus (swine flu) immunization program was implicated as the trigger of many GBS cases. Some studies reported a sevenfold increase in the number of GBS cases following immunization. Because of the large number of GBS cases the program was halted. Another study reported a smaller increase in GBS cases (about 1 extra person per 1,000,000 persons vaccinated each year) following administration of influenza vaccine for more common human strains of influenza during the 1992-93 and 1993-94 seasons.

The greater-than-expected number of GBS cases associated with the 1976 swine flu vaccine led to a concern by some patients that influenza immunization shots or even other